their skin biology but are also underrepresented in therapeutic clinical trials, preventing complete understanding of side effects. 4,9,10,11,12

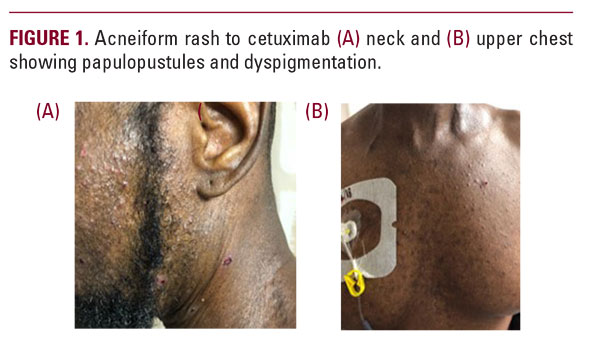

EGFR-inhibitor rash in African American patients has only been reported a few times previously. One case was of a 61-year-old male with oropharyngeal cancer also treated with cetuximab who developed a mild facial acneiform rash after the second cycle of treatment, that progressed in severity with continued treatment. He was similarly treated with doxycycline with improvement.2 The second case was of a 41-year-old African American female who developed a milder presentation after six cycles of lapatinib and was treated only with low potency topical steroids. In both cases, treatment was continued, although in the first case, dose was held for one week.6 Although one case eluded to the challenges in treating this rash in patients of skin of color or darker skin types, both cases were treated similarly according to known rash algorithm.

One of the main challenges in treating this rash in different patient populations is inherent biologic differences in skin of African Americans and Caucasians.9,13 Although the acneiform rash from EGFR-inhibitors has a different pathogenesis from typical acne with inflammation beginning in the pilosebaceous unit, we know that African Americans have a higher baseline density of P. acnes, and larger sebaceous glands with increased sebum secretion.8,9,12,13 Consequently, skin of color displays substantial histological inflammation even around comedones that are not clinically inflamed.8,9,12 This heightened inflammatory response may be why African Americans with even mild to moderate acne develop post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH).9,12,13 African Americans also have an increased number of fibroblasts, as well as larger fibroblasts, resulting in an increased prevalence of keloids.13,15

These inflammatory mediators can also stimulate tyrosinase activity and subsequent melanin synthesis.11 It is known that the differences in skin color are not due to the number of melanocytes, but rather the activity of tyrosinase in melanosomes, the number, size, and aggregation of melanosomes within melanocytes, and the efficiency of melanosome transfer from melanocyte to keratinocyte.9,11,13 In African Americans, the number of melanosomes transferred to keratinocytes is significantly higher, melanosomes are more active in producing melanin, and they are larger and present in all layers of the epidermis.9,13 PIH is more prevalent in African Americans due to these increased melanosomes which exhibit labile responses to irritation and injury.11,13 Other factors that may contribute to worsening PIH include increased skin sensitivity in African Americans thought to be due to impaired barrier function/increased transepidermal water loss, which may increase irritation after topical acne products such as retinoids.8,12,13 Furthermore, skin care practices including use of hair emollients and heavy oils leading to “pomade acne” and the increased incidence of other follicular skin and hair disorders in the African American population such as acne keloidalis may also contribute to worsening acneiform rash in patients receiving EGFR inhibitors.8,9,12,13,14

CONCLUSION

Treatment of EGFR-inhibitor induced rash in patients with skin of color can present both cultural challenges, due to skin care product use, and pathophysiologic challenges, due to differences in skin biology and sensitivity.2,4,8 Delays in treatment and misdiagnoses may lead to sequelae such as PIH and keloids which is more prevalent in this population.9 Reducing skin irritation and xerosis, which may adversely affect darker skin, is a key goal in treating rash in skin of color.8 Further studies are needed to evaluate EGFR-inhibitor rash presentation and treatment outcomes with standard algorithm in African Americans to determine if the typical management approach needs to be modified in this patient population.7

DISCLOSURES

ANG does not have any relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

SJN served as a consultant/speaking role for Kyowa Kirin and

Array Biopharma.

REFERENCES

1. Solomon BM, Jatoi A. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitorinduced rash: a consecutive patient series that illustrates the need for rigorous palliative trials. J Palliat Med 2011; 14(2): 153-156.

2. Waris W, et al. Severe cutaneous reaction to cetuximab with possible association with the use of over-the-counter skin care products in a patient with oropharyngeal cancer. Cutan Ocul Toxicol 2009; 28(1): 41-44.

3. Bachet JB, et al. Folliculitis induced by EGFR inhibitors, preventative and curative efficacy of tetracyclines in the management and incidence rates according to the type of EGFR inhibitor administered: a systematic literature review. The Oncologist 2012; 17: 555-568.

4. Burtness B, et al. NCCN task force report: management of dermatologic and other toxicities associated with EGFR inhibition in patients with cancer. JNCCN 2009; 7(1): 5-21.

5. Leidner RS, et al. Genetic abnormalities of the EGFR pathway in african american patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 5620-5626.

6. Friedman MD, Lacouture M, Dang C. Dermatologic adverse events associated with use of adjuvant lapatinib in combination with paclitaxel and trastuzumab for HER2-positive breast cancer: a case series analysis. Clin Breast Cancer 2016; 16(3): 69-74.

7. Lacouture ME, et al. Dermatologic toxicity occurring during anti-EGFR mono

2. Waris W, et al. Severe cutaneous reaction to cetuximab with possible association with the use of over-the-counter skin care products in a patient with oropharyngeal cancer. Cutan Ocul Toxicol 2009; 28(1): 41-44.

3. Bachet JB, et al. Folliculitis induced by EGFR inhibitors, preventative and curative efficacy of tetracyclines in the management and incidence rates according to the type of EGFR inhibitor administered: a systematic literature review. The Oncologist 2012; 17: 555-568.

4. Burtness B, et al. NCCN task force report: management of dermatologic and other toxicities associated with EGFR inhibition in patients with cancer. JNCCN 2009; 7(1): 5-21.

5. Leidner RS, et al. Genetic abnormalities of the EGFR pathway in african american patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 5620-5626.

6. Friedman MD, Lacouture M, Dang C. Dermatologic adverse events associated with use of adjuvant lapatinib in combination with paclitaxel and trastuzumab for HER2-positive breast cancer: a case series analysis. Clin Breast Cancer 2016; 16(3): 69-74.

7. Lacouture ME, et al. Dermatologic toxicity occurring during anti-EGFR mono