INTRODUCTION

Acne vulgaris, a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by papules, pustules, comedones, and nodules, imposes significant physical, psychological, and economic burdens.1 Acne affects 85% of adolescents but can continue to trouble adults1; it may also newly develop in adulthood or reappear after resolving.2

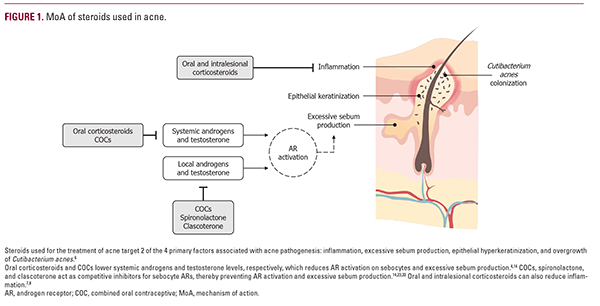

The 4 primary factors driving acne pathogenesis are inflammation, increased sebum production, epithelial hyperkeratinization, and overgrowth of Cutibacterium acnes.1 Androgens are the leading group of hormones involved in acne development, and testosterone, androstenedione, and cortisol levels correlate with disease severity.3 Recommended first-line treatment for acne vulgaris includes topical or systemic retinoids, topical or oral antimicrobials, and/or topical benzoyl peroxide (BPO), but alternative treatment options include steroids and steroidal molecules such as corticosteroids, combined oral contraceptives (COCs), and spironolactone.1 Steroids and related molecules are a valuable therapeutic class for acne because they address the hormonal aspects of acne pathogenesis while providing alternative treatment options for patients with acne refractory to antibiotics and other conventional treatments.1,4

This review provides an overview of the recommended use, mechanisms of action, and clinical evidence for steroids and steroidal molecules used for the treatment of acne. Key clinical considerations for the appropriate use of these treatments in patients with acne are also summarized.

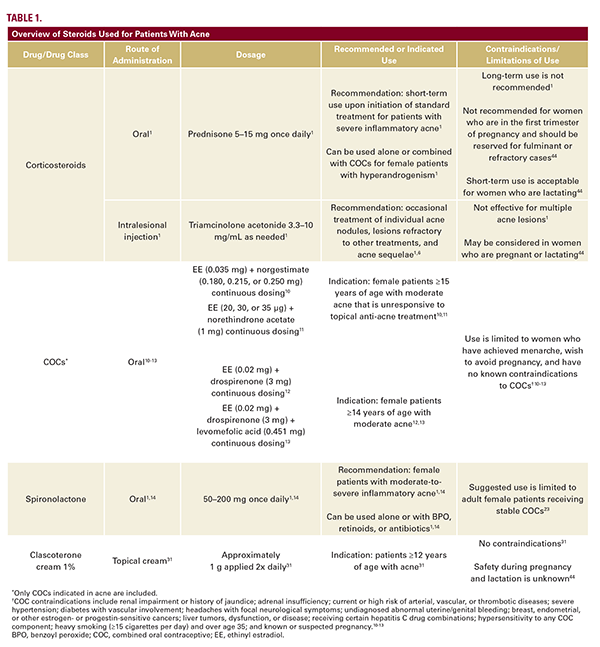

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids used for acne treatment comprise oral corticosteroids and intralesional corticosteroid injections (Table 1).1 Oral corticosteroids, mainly prednisone, are recommended upon initiation of standard treatment for patients with severe inflammatory acne,1 but their long-term adverse event (AE) profile precludes their use as primary acne therapies.1,5 Low-dose oral corticosteroids are recommended alone or in combination with COCs for patients with hyperandrogenism.1 Intralesional corticosteroid injections (triamcinolone acetonide 3.3-10 mg/mL) are recommended for the occasional treatment of individual acne nodules, lesions refractory to other treatments, and acne sequelae.1,6

Oral corticosteroids act as potent anti-inflammatory agents (Figure 1).7 By inhibiting pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) production, oral corticosteroids also lower androgen

levels, suppress activation of androgen receptors (ARs) on sebocytes, and prevent excessive sebum production.4 Intralesional corticosteroids also induce local vasoconstriction, which reduces inflammation.8

Low-dose prednisone (5-15 mg/day) alone or with COCs is effective for the treatment of acne.1 The most common AEs with oral corticosteroid use across all disease states (including acne) are fractures, gastric conditions (eg, epigastric discomfort), weight gain, hyperglycemia, and ocular conditions (eg, ocular hypertension and acute angle glaucoma).1,5 Slow tapering of oral corticosteroids is recommended when switching therapies to minimize the risk of relapse.1 Prolonged exposure to systemic steroids can also result in steroid-induced acne.9

Intralesional corticosteroid injections are effective for occasional acne lesions but unsuccessful for the management of multiple lesions.1 Common AEs with intralesional corticosteroid injections include infection, impaired wound healing, allergic skin reactions (eg, contact dermatitis, angioedema, and urticaria), anaphylaxis, and sterile abscess.1 Corticosteroid overdose at the injection site can result in atrophy, pigmentary changes, telangiectasias, and hypertrichosis.1 Systemic corticosteroid absorption can also occur with intralesional corticosteroid injections; hence the development of steroid acne is also a common occurrence with intralesional injections.1

Combined Oral Contraceptives

COCs are a systemic treatment option recommended for patients with moderate-to-severe acne as an alternative to first-line treatment with topical BPO, retinoids, or antibiotics.1 COC use is limited to female patients who have achieved menarche and want or agree to avoid pregnancy (Table 1).10-14 Formulations containing low-dose ethinyl estradiol (EE; 20-35 µg) and an antiandrogenic progestin are recommended.4,14 In the US, 4 COCs are indicated for acne treatment in women greater than or equal to 14 years of age: EE/norgestimate, EE/norethindrone acetate, EE/drospirenone, and EE/drospirenone/levomefolic acid.10-13

Both components of the combined contraception pill, estrogen and progesterone, work together to decrease the levels of androgens throughout the body through various mechanisms, including the regulation of sex hormone-binding globulin, estrogen receptor expression, gonadotropin secretion, 5α-reductase activity, and ACTH levels (Figure 1).15 Conversely, progesterone-only oral contraceptives and intrauterine devices can have androgenic effects and exacerbate acne, so these contraceptive methods are not recommended for women with acne.16,17

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) support the treatment benefit of COCs vs placebo for the clearance of inflammatory and noninflammatory acne lesions.1,18 There are no significant differences in efficacy among different COC formulations used for the treatment of acne.19

The most common AEs with COCs in clinical trials were nausea, breast enlargement, headache, and weight gain.14 Weight gain associated with COCs during early treatment may be due to the EE component, which can induce fluid retention; however, overall, there is insufficient clinical trial evidence supporting a relationship between COC use and weight gain.20 These AEs are less frequent with newer-generation COCs that contain lower EE levels and less androgenic progestins.17,21 The risk of cardiovascular events (including venous thromboembolism and myocardial infarction) is increased in patients with risk factors such as smoking, diabetes, or hypertension.1 A marginally increased risk of breast and ovarian cancers with COC use is reported but controversial.21

Spironolactone

Oral spironolactone is a potassium-sparing diuretic indicated for the treatment of heart failure, hypertension, edema, and primary

hyperaldosteronism22 and is used in clinical practice for the treatment of systemic arterial hypertension and heart failure.14,23 Oral spironolactone (50-200 mg orally daily) is also used off-label for adults with acne (Table 1).1,14 It is recommended as a monotherapy or add-on therapy to BPO, retinoids, or antibiotics for female patients with moderate-to-severe inflammatory acne.1,14 Because of potential feminizing effects in male patients and also male fetuses in the case of pregnant patients, spironolactone use is ideally limited to adult female patients with treatment-persistent or late-onset acne who are receiving stable COCs.23

Spironolactone is a nonselective mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist with a moderate impact on progesterone and ARs (Figure 1).23 Similar to COCs, spironolactone has systemic anti-androgen activity throughout the body; in the skin, spironolactone competes with dihydrotestosterone for binding to ARs on sebocytes, thus reducing excess sebum production.23

Current treatment guidelines support the use of oral spironolactone in select women with acne based on clinical experience and expert opinion, but there is little clinical evidence.1,21,23 The efficacy of spironolactone plus COCs is similar to that of COCs alone.23 However, low-dose oral spironolactone (25-50 mg/day) plus BPO was more effective than placebo plus BPO in adult women with acne.24 Long-term oral spironolactone treatment also resulted in durable acne clearance (during a >2-year follow-up period) in 96% of patients in 1 case series.25 The FASCE and SAFA studies will be the first Phase 3, double-blind RCTs to evaluate oral spironolactone as part of combination therapy for acne in adult women.26-29

In female patients, long-term oral spironolactone treatment is generally well tolerated, and AEs are mainly dose related.1,23,25 One study was discontinued prematurely in male patients due to gynecomastia.1 The most common AEs with oral spironolactone are menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness and enlargement, dizziness/vertigo/lightheadedness, headache, nausea with/without vomiting, weight gain, abdominal pain, polyuria, and fatigue/lethargy.23 The incidence of menstrual irregularities is lower with spironolactone plus COCs compared with spironolactone alone.23

Hyperkalemia is a rare but serious AE potentially associated with spironolactone use.1 Risk of hyperkalemia with spironolactone treatment may increase with age; hypertension; existing hepatic, renal, or adrenal disease; or concomitant use of other potassium-sparing medications.14 Routine monitoring of serum potassium levels is recommended for patients with these risk factors but is not otherwise required.1,23 Monitoring is also recommended for patients with persistent nausea, fatigue, and muscle weakness, which may indicate hyperkalemia.23

Clascoterone (Cortexolone 17alpha-propionate)

Topical clascoterone cream 1% is a first-in-class topical androgen inhibitor approved for the treatment of acne in patients greater than or equal to 12 years of age (Table 1).30,31 Clascoterone acts as a competitive AR inhibitor but is rapidly metabolized by enzymes in the skin to cortexolone, a natural intermediate in the glucocorticoid synthesis pathway that has little to no systemic activity of its own (Figure 1).30,32,33

Topical treatment with clascoterone cream 1% resulted in improvement in acne over vehicle treatment in patients with acne in 2 randomized, double-blind, pivotal Phase 3 studies34 and a pooled data analysis of trial patients greater than or equal to 12 years of age, the population for which clascoterone cream 1% is approved.35

Clinical trial data support the safety and tolerability of clascoterone in adolescents and adults with acne.34,36 In Phase 3 clinical trials, the AE profile of clascoterone cream 1% was similar to that of vehicle cream for up to 12 months of treatment. The most common AEs in both arms of the Phase 3 trials were nasopharyngitis, headache, and oropharyngeal pain.34 There was no accumulation or increase in AEs over time or new safety findings in the 9-month, open-label extension portion of the two Phase 3 trials.37,38 Laboratory findings of hyperkalemia were observed in a pooled analysis of eight Phase 1 or Phase 2 studies, including 1 study that used an unapproved clascoterone 7.5% solution formulation and other studies that used supratherapeutic doses39; and laboratory evidence of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression was observed in a Phase 2a study in which patients applied 4- to 6-fold more clascoterone cream 1% than the recommended dose of 1 g twice daily.31,36 These laboratory findings were observed mainly in younger patients, but no exposure-response relationships were established, and no laboratory monitoring of either potassium or adrenal status is recommended in the approved labeling for clascoterone cream 1%.31,36,39

Clinical Considerations for Steroid Use in Patients With Acne

The selection of steroidal treatment options for acne should be personalized based on the patient's demographics (age and skin of color [SOC]), concurrent clinical conditions, and preferred route of administration.2,40-44

Adolescent or Adult Acne

Due to safety concerns, the use of spironolactone and COCs is limited in adolescents with acne.1,45 Spironolactone is recommended only for adolescents with frequent acne breakouts and those who require long-term antibiotics, have contraindications or intolerance to retinoids, or have hyperandrogenism.45 The reduction in estrogen levels with

COCs can negatively affect bone mass, which peaks during adolescence and young adulthood.1 Therefore, COCs should be avoided within 2 years of first starting menses and in patients <14 years of age.1 Currently, clascoterone is the only steroid-based option approved for adolescents greater than or equal to 12 years of age and adults with moderate-to-severe facial acne.31

Darker Skin Color

Patients with darker skin color are underrepresented in acne clinical trials.46 Although acne pathogenesis is similar regardless of skin color, the clinical presentation and disease course of acne, including common sequelae, differ between patients with and without SOC.42 For example, patients with SOC frequently develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which may be exacerbated by irritation from topical therapies.42 Use of steroids is recommended for patients with SOC who have severe papulopustular or nodulocystic acne.42

Androgen Levels

Excessive androgen levels are not consistently observed in patients with acne.47 Patients with persistent acne, as opposed to late-onset acne, frequently have marked hyperandrogenism, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and other hormonal abnormalities, suggesting they might benefit from androgen-targeting therapies.48 However, anti-androgens, including steroids, can be effective irrespective of serum androgen levels.47

Patients Who Are Pregnant or Lactating

There is limited safety data on steroid-based acne treatments in pregnant and lactating patients.44 Oral corticosteroids, COCs, and spironolactone are either contraindicated or not recommended for pregnant or lactating patients (Table 1).40,44 Therefore, the use of oral corticosteroids for the treatment of acne in pregnant or lactating patients should be limited to fulminant or refractory cases.44 Spironolactone should also be avoided during pregnancy but can be used while lactating.40 Most topical agents are considered low risk for lactating patients.40 Intralesional corticosteroid injections and clascoterone may be considered during pregnancy and lactation due to their minimal systemic absorption; however, no data are available to determine the risk.40,44,47

Route of Administration

Neither topical nor oral treatments are consistently associated with improved adherence or persistence in patients with acne.49 Therefore, treatment selection should consider patients' preferences and habits to improve their adherence.41,49 For example, topical treatments may better suit patients who routinely forget to take daily pills.41 Conversely, patients who find topical treatments burdensome may benefit from an oral treatment.41

CONCLUSION

Overall, oral and topical steroidal approaches are effective in the management of acne. Healthcare providers should discuss efficacy, safety, and other considerations with their patients to select the most appropriate therapy. Shared decision-making should also include discussions of patient characteristics and clinical circumstances, in which it is important to tailor steroid use individually.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Nitish Chaudhari PhD, of AlphaBioCom, a Red Nucleus company, and funded by Sun Pharma.

REFERENCES

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945-973.

- Kutlu O, Karadag AS, Wollina U. Adult acne versus adolescent acne: a narrative review with a focus on epidemiology to treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98(1):75-83.

- Borzyszkowska D, Niedzielska M, Kozlowski M, et al. Evaluation of hormonal factors in acne vulgaris and the course of acne vulgaris treatment with contraceptive-based therapies in young adult women. Cells. 2022;11(24):4078.

- Dash G, Patil A, Kroumpouzos G, et al. Hormonal therapies in the management of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21(6):618-623.

- Manson SC, Brown RE, Cerulli A, Vidaurre CF. The cumulative burden of oral corticosteroid side effects and the economic implications of steroid use. Respir Med. 2009;103(7):975-994.

- Kurokawa I, Layton AM, Ogawa R. Updated treatment for acne: targeted therapy based on pathogenesis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11(4):1129- 1139.

- Dall'oglio F, Puglisi DF, Nasca MR, et al. Acne fulminans. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2020;155(6):711-718.

- Gallagher T, Taliercio M, Nia JK, et al. Dermatologist use of intralesional triamcinolone in the treatment of acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(12):41-43.

- Purdy S, de Berker D. Acne. BMJ. 2006;333(7575):949-953.

- ORTHO TRI-CYCLEN TABLETS; ORTHO-CYCLEN TABLETS (norgestimate/ethinyl estradiol) [physicians' package insert]. Raritan, NJ: Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc.; 2011.

- ESTROSTEP Fe (norethindrone acetate and ethinyl estradiol tablets, USP and ferrous fumarate tablets) [full prescribing information]. Irvine, CA: Allergan USA, Inc.; 2017.

- YAZ (drospirenone and ethinyl estradiol) tablets [full prescribing information]. Wayne, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2010.

- BEYAZ (drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol/levomefolate calcium tablets and levomefolate calcium tablets), for oral use [full prescribing information]. Wayne, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2012.

- Costa C, Bagatin E, Yang Z, et al. Systemic pharmacological treatments for acne: an overview of systematic reviews (protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021(11):CD014917.

- Slopien R, Milewska E, Rynio P, et al. Use of oral contraceptives for management of acne vulgaris and hirsutism in women of reproductive and late reproductive age. Prz Menopauzalny. 2018;17(1):1-4.

- Pakey J, Nassim JS, Reynolds RV. Hormonal intrauterine devices and acne. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139(5):919-921.

- Tyler KH, Zirwas MJ. Contraception and the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(6):1022-1029.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD004425.

- Barbieri JS, Mitra N, Margolis DJ, et al. Influence of contraception class on incidence and severity of acne vulgaris. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(6):1306- 1312.

- Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1):CD003987.

- Marson JW, Baldwin HE. An overview of acne therapy, part 2: hormonal therapy and isotretinoin. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37(2):195-203.

- ALDACTONE (spironolactone) tablets for oral use [full prescribing information]. New York, NY: Pfizer, Inc.; 2018.

- Layton AM, Eady EA, Whitehouse H, et al. Oral spironolactone for acne vulgaris in adult females: a hybrid systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(2):169-191.

- Patiyasikunt M, Chancheewa B, Asawanonda P, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of low-dose spironolactone and topical benzoyl peroxide in adult female acne: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Dermatol. 2020;47(12):1411-1416.

- Garg V, Choi JK, James WD, et al. Long-term use of spironolactone for acne in women: a case series of 403 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(5):1348-1355.

- Poinas A, Lemoigne M, Le Naour S, et al. FASCE, the benefit of spironolactone for treating acne in women: study protocol for a randomized double-blind trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):571.

- Randomized double-blind study on the benefit of spironolactone for treating acne of adult woman (FASCE). ClinicalTrials.gov. Available at: https:// clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03334682. Accessed January 27, 2023.

- Renz S, Chinnery F, Stuart B, et al. Spironolactone for Adult Female Acne (SAFA): protocol for a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III randomised study of spironolactone as systemic therapy for acne in adult women. BMJ Open. 2021;11(8):e053876.

- Spironolactone for adult female acne. ISRCTN. Available at: https://www. isrctn.com/ISRCTN12892056. Accessed January 27, 2023.

- Mazzetti A, Moro L, Gerloni M, Cartwright M. A phase 2b, randomized, double-blind vehicle controlled, dose escalation study evaluating clascoterone 0.1%, 0.5%, and 1% topical cream in subjects with facial acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(6):570.

- WINLEVI (clascoterone) cream, for topical use [full prescribing information]. Cranbury, NJ: Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.; 2022.

- Celasco G, Moro L, Bozzella R, et al. Biological profile of cortexolone 17alpha-propionate (CB-03-01), a new topical and peripherally selective androgen antagonist. Arzneimittelforschung. 2004;54(12):881-886.

- Ferraboschi P, Legnani L, Celasco G, et al. A full conformational characterization of antiandrogen cortexolone-17a-propionate and related compounds through theoretical calculations and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Med Chem Commun. 2014;5:904-914.

- Hebert A, Thiboutot D, Stein Gold L, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical clascoterone cream, 1%, for treatment in patients with facial acne: two phase 3 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(6):621-630.

- Hebert A, Eichenfield L, Thiboutot D, et al. Efficacy and safety of 1% clascoterone cream in patients aged ≥12 years with acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22(2):174-181.

- Mazzetti A, Moro L, Gerloni M, et al. Pharmacokinetic profile, safety, and tolerability of clascoterone (cortexolone 17-alpha propionate, CB-03-01) topical cream, 1% in subjects with acne vulgaris: an open-label phase 2a study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(6):563.

- Eichenfield L, Hebert A, Stein Gold L, et al. Open-label, long-term extension study to evaluate the safety of clascoterone (CB-03-01) cream, 1% twice daily, in patients with acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):477- 485.

- Eichenfield LF, Hebert AA, Stein Gold L, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of twice-daily topical clascoterone cream 1% in patients =>12 years of age with acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22(8):810-816.

- Del Rosso JQ, Stein Gold L, Squittieri N, et al. Is there a clinically relevant risk of hyperkalemia with topical clascoterone treatment? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(6):20-24.

- Eichenfield DZ, Sprague J, Eichenfield LF. Management of acne vulgaris: a review. JAMA. 2021;326(20):2055-2067.

- Haney B. Acne: what primary care providers need to know. Nurse Pract. 2022;47(10):9-13.

- Alexis A, Woolery-Lloyd H, Andriessen A, et al. Racial/ethnic variations in acne: a practical algorithm for treatment and maintenance, including skincare recommendations for skin of color patients with acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21(11):s13223-s132214.

- Radi R, Gold S, Acosta JP, et al. Treating acne in transgender persons receiving testosterone: a practical guide. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(2):219-229.

- Ly S, Kamal K, Manjaly P, et al. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation: a narrative review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13(1):115- 130.

- Dhurat R, Shukla D, Lim RK, et al. Spironolactone in adolescent acne vulgaris. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(1):e14680.

- Sevagamoorthy A, Sockler P, Akoh C, Takeshita J. Racial and ethnic diversity of US participants in clinical trials for acne, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis: a comprehensive review. J Dermatol Treat. 2022;33(8):3086-3097.

- Bansal P, Sardana K, Sharma L, et al. A prospective study examining isolated acne and acne with hyperandrogenic signs in adult females. J Dermatol Treat. 2021;32(7):752-755.

- Sardana K, Bansal P, Sharma LK, et al. A study comparing the clinical and hormonal profile of late onset and persistent acne in adult females. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(4):428-433.

- Tobiasz A, Nowicka D, Szepietowski JC. Acne vulgaris-novel treatment options and factors affecting therapy adherence: a narrative review. J Clin Med. 2022;11(24):7535.

AUTHOR CORRESPONDENCE

Loree Easley PA-C loree.easley@yahoo.com