INTRODUCTION

Dermatophytoses, fungal infections of the skin, hair, and nails, affect approximately 25% of the global population, and reports of antifungal therapy-resistant infections have risen over the past decade.1 A major contributor to this trend is the widespread practice of empirically treating suspected fungal infections without diagnostic confirmation.1

Misdiagnosis is common, as dermatophytoses exhibit considerable clinical variability and mimic numerous inflammatory dermatoses, including secondary syphilis, annular psoriasis, and pityriasis rosea.2 Reflecting these challenges, the American Academy of Dermatology's Choosing Wisely campaign recommends avoiding empiric oral antifungal therapy without confirmatory testing for suspected onychomycosis.3 Nevertheless, dermatologists frequently prescribe antifungals without confirmatory testing.4 This review examines the diagnostic gaps that contribute to inappropriate antifungal prescribing, the role these practices play in antifungal resistance (AFR), and stewardship strategies to improve accuracy and treatment outcomes.

Diagnostic Gaps in Dermatophytoses

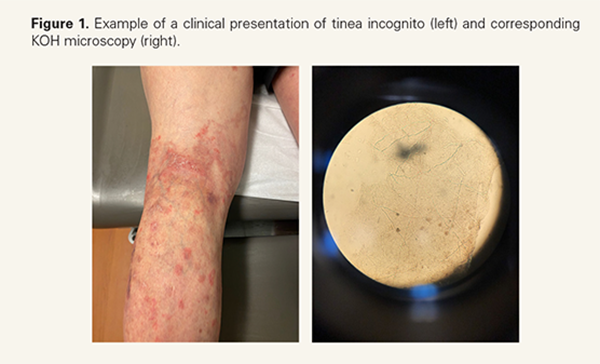

The diagnostic evaluation of dermatophytoses includes potassium hydroxide (KOH) microscopy, fungal culture, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, and histopathology.1 KOH preparations provide inexpensive, rapid diagnosis, yet they are frequently underutilized in the clinical setting1,4 (Figure 1). In a survey of 308 dermatologists, 20.9% "rarely" or "never" performed fungal examinations prior to prescribing antifungals, and 19.9% reported "sometimes" doing

Misdiagnosis is common, as dermatophytoses exhibit considerable clinical variability and mimic numerous inflammatory dermatoses, including secondary syphilis, annular psoriasis, and pityriasis rosea.2 Reflecting these challenges, the American Academy of Dermatology's Choosing Wisely campaign recommends avoiding empiric oral antifungal therapy without confirmatory testing for suspected onychomycosis.3 Nevertheless, dermatologists frequently prescribe antifungals without confirmatory testing.4 This review examines the diagnostic gaps that contribute to inappropriate antifungal prescribing, the role these practices play in antifungal resistance (AFR), and stewardship strategies to improve accuracy and treatment outcomes.

Diagnostic Gaps in Dermatophytoses

The diagnostic evaluation of dermatophytoses includes potassium hydroxide (KOH) microscopy, fungal culture, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, and histopathology.1 KOH preparations provide inexpensive, rapid diagnosis, yet they are frequently underutilized in the clinical setting1,4 (Figure 1). In a survey of 308 dermatologists, 20.9% "rarely" or "never" performed fungal examinations prior to prescribing antifungals, and 19.9% reported "sometimes" doing

so.4 The belief that clinical examination alone is sufficient remains a major barrier, despite evidence demonstrating the high rate of visual misclassification caused by the varied presentations of dermatophytoses.4 For example, Yadgar et al conducted an imagebased survey, in which dermatologists were asked to categorize 13 clinical images as either fungal or non-fungal infections; only 8 out of 13 cases were correctly categorized more than half of the time, with only one case achieving >90% diagnostic accuracy.2

Diagnostic confirmation is even less common in onychomycosis, as a recent study by Gupta et al demonstrated that among 120,000 patients with suspected onychomycosis, only around 10% of patients who received oral antifungals and 16% who received topical antifungals underwent confirmatory testing.5 This gap may be attributed to the higher costs of KOH preparation and periodic acid- Schiff (PAS) evaluation compared to empirical terbinafine treatment.6 However, recent studies report that confirmatory testing may ultimately be less expensive than the downstream costs associated with misdiagnosis and treatment failure.5,6

Consequences of Empiric Antifungal Treatment

Empiric antifungal treatment for non-fungal conditions delays accurate diagnosis and care while contributing to selective pressure that fosters resistance.2,7 AFR has become increasingly recognized globally, with terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton rubrum and T. indotineae most prominently implicated.1 The first US case of T. indotineae resistant to oral terbinafine was reported in 2023, confirming AFR as a worldwide issue.1 Resistance has since been documented across both fungicidal (eg, terbinafine) and fungistatic (eg, azoles) drug classes, reinforcing the need for stewardship.1

In addition to empiric use, prescribing antifungals for non-fungal conditions, such as seborrheic dermatitis (SD), adds to unnecessary exposure and may promote AFR. SD is a chronic skin disorder affecting areas of the body rich in sebaceous glands.8 Though Malassezia yeast overgrowth is one of multiple driving factors of SD, in addition to epidermal skin barrier disruption and a dysregulated inflammatory response, it is not considered a true fungal infection; yet topical ketoconazole (1% over the counter (OTC); 2% prescription) shampoo remains first-line therapy for SD of the scalp.8 Studies have reported elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) in Malassezia isolates for azoles and terbinafine in SD patients,

Diagnostic confirmation is even less common in onychomycosis, as a recent study by Gupta et al demonstrated that among 120,000 patients with suspected onychomycosis, only around 10% of patients who received oral antifungals and 16% who received topical antifungals underwent confirmatory testing.5 This gap may be attributed to the higher costs of KOH preparation and periodic acid- Schiff (PAS) evaluation compared to empirical terbinafine treatment.6 However, recent studies report that confirmatory testing may ultimately be less expensive than the downstream costs associated with misdiagnosis and treatment failure.5,6

Consequences of Empiric Antifungal Treatment

Empiric antifungal treatment for non-fungal conditions delays accurate diagnosis and care while contributing to selective pressure that fosters resistance.2,7 AFR has become increasingly recognized globally, with terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton rubrum and T. indotineae most prominently implicated.1 The first US case of T. indotineae resistant to oral terbinafine was reported in 2023, confirming AFR as a worldwide issue.1 Resistance has since been documented across both fungicidal (eg, terbinafine) and fungistatic (eg, azoles) drug classes, reinforcing the need for stewardship.1

In addition to empiric use, prescribing antifungals for non-fungal conditions, such as seborrheic dermatitis (SD), adds to unnecessary exposure and may promote AFR. SD is a chronic skin disorder affecting areas of the body rich in sebaceous glands.8 Though Malassezia yeast overgrowth is one of multiple driving factors of SD, in addition to epidermal skin barrier disruption and a dysregulated inflammatory response, it is not considered a true fungal infection; yet topical ketoconazole (1% over the counter (OTC); 2% prescription) shampoo remains first-line therapy for SD of the scalp.8 Studies have reported elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) in Malassezia isolates for azoles and terbinafine in SD patients,