Pediatric periorificial dermatitis (POD) is a papulopustular facial eruption that can be exacerbated by topical steroid use.1 Crisaborole (Eucrisa®) is a relatively new steroid-sparing topical agent approved for treatment of atopic dermatitis. We present a first report of exacerbation of pediatric POD by crisaborole.

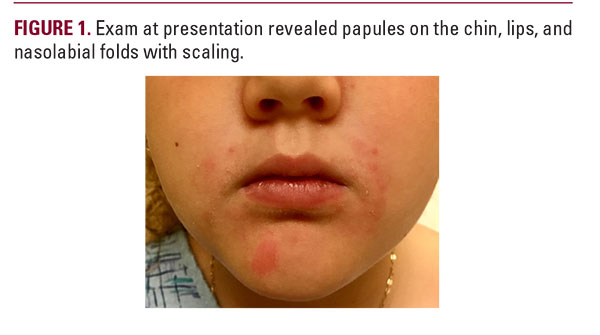

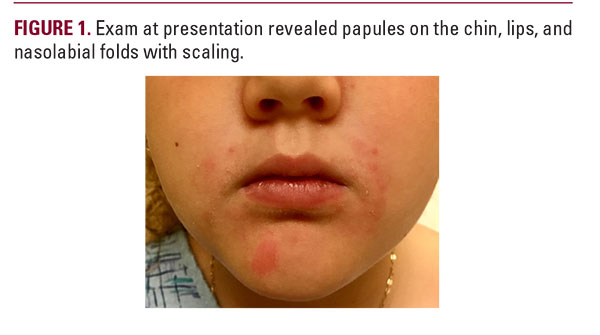

A seven-year-old girl with atopic dermatitis, asthma, and seasonal allergies presented with an erythematous papular peri-orofacial eruption. This was preceded by a much milder intermittently pruritic perioral rash that began at age four when the patient started using a steroid inhaler with a spacer and mouthpiece. Over-the-counter treatments did not resolve the rash, so her pediatrician prescribed crisaborole twice daily. After three weeks of crisaborole the eruption worsened to the point that dermatologic evaluation was sought (Figure 1). She denied recent topical steroid use, or changes in medications, food, or skin care. Physical exam revealed non-tender pink papules on the chin, cutaneous lips, and nasolabial folds with mild scaling and occasional pinpoint pustules. Vermillion lip and periocular areas were uninvolved. We recommended stopping crisaborole and starting metronidazole cream twice daily. We also advised regularly cleaning the parts of the inhaler that touch the patient’s face, and to gently wash the perioral area after each use. The rash improved significantly within weeks of starting metronidazole and stopping crisaborole. Pediatric POD classically presents as a papulopustular eruption surrounding the mouth, sometimes extending to the perinasal and/or periorbital regions, and is closely linked to both topical and inhaled steroid use.1 Most reported cases involve Caucasian females, with a mean age of six.2 POD is often misdiagnosed as atopic dermatitis and treated with topical steroids, which can exacerbate the eruption. POD treatment generally involves topical and/or oral antibiotics, with metronidazole showing greatest efficacy.3 Other antibiotics including clindamycin, erythromycin, and sulfacetamide have shown success, as have newer therapies such as azelaic acid cream.4 Although steroids can worsen POD, medically necessary steroids such as inhalers can be continued with care to minimize contact with involved skin.3

In December 2016 the FDA approved crisaborole ointment for treatment of mild to moderate eczema in patients aged two and older. Unlike corticosteroids, crisaborole’s mechanism of action involves inhibiting phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE-4), which prevents it from degrading cyclic adenosine monophosphate and inducing inflammation.5 To date, a few studies have described its use in non-atopic disorders such as seborrheic dermatitis.6 Although its mechanism of action differs from that of corticosteroids, it appears that crisaborole too can exacerbate pediatric POD.

A seven-year-old girl with atopic dermatitis, asthma, and seasonal allergies presented with an erythematous papular peri-orofacial eruption. This was preceded by a much milder intermittently pruritic perioral rash that began at age four when the patient started using a steroid inhaler with a spacer and mouthpiece. Over-the-counter treatments did not resolve the rash, so her pediatrician prescribed crisaborole twice daily. After three weeks of crisaborole the eruption worsened to the point that dermatologic evaluation was sought (Figure 1). She denied recent topical steroid use, or changes in medications, food, or skin care. Physical exam revealed non-tender pink papules on the chin, cutaneous lips, and nasolabial folds with mild scaling and occasional pinpoint pustules. Vermillion lip and periocular areas were uninvolved. We recommended stopping crisaborole and starting metronidazole cream twice daily. We also advised regularly cleaning the parts of the inhaler that touch the patient’s face, and to gently wash the perioral area after each use. The rash improved significantly within weeks of starting metronidazole and stopping crisaborole. Pediatric POD classically presents as a papulopustular eruption surrounding the mouth, sometimes extending to the perinasal and/or periorbital regions, and is closely linked to both topical and inhaled steroid use.1 Most reported cases involve Caucasian females, with a mean age of six.2 POD is often misdiagnosed as atopic dermatitis and treated with topical steroids, which can exacerbate the eruption. POD treatment generally involves topical and/or oral antibiotics, with metronidazole showing greatest efficacy.3 Other antibiotics including clindamycin, erythromycin, and sulfacetamide have shown success, as have newer therapies such as azelaic acid cream.4 Although steroids can worsen POD, medically necessary steroids such as inhalers can be continued with care to minimize contact with involved skin.3

In December 2016 the FDA approved crisaborole ointment for treatment of mild to moderate eczema in patients aged two and older. Unlike corticosteroids, crisaborole’s mechanism of action involves inhibiting phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE-4), which prevents it from degrading cyclic adenosine monophosphate and inducing inflammation.5 To date, a few studies have described its use in non-atopic disorders such as seborrheic dermatitis.6 Although its mechanism of action differs from that of corticosteroids, it appears that crisaborole too can exacerbate pediatric POD.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

1.Kellen, R, Silverberg, N. Pediatric periorifical dermatitis. Cutis. 2017 December;100(6):385-388

2. Goel, N. S., Burkhart, C. N. and Morrell, D. S. (2015), Pediatric periorificial dermatitis: clinical course and treatment outcomes in 222 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 May-Jun;32(3):333-6. doi:10.1111/pde.12534

3. Green B, Morrell DS. Persistent facial dermatitis: pediatric perioral dermatitis. Pediatr Ann. 2007;36(12):796–798.

4. Jansen T, Melnik BC, Schadenodorf D. Steroid-induced periorificial dermatitis in children—clinical features and response to azelaic acid. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27(2):137–142.

5. Zebda, Rema et al. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 78(3):S43-S52.

6. Liu D, Chow P, Strawn S, Rajpara A, Wang T, Aires D. Chronic nasolabial fold seborrheic dermatitis successfully controlled with crisaborole. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(5):577-578.

2. Goel, N. S., Burkhart, C. N. and Morrell, D. S. (2015), Pediatric periorificial dermatitis: clinical course and treatment outcomes in 222 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 May-Jun;32(3):333-6. doi:10.1111/pde.12534

3. Green B, Morrell DS. Persistent facial dermatitis: pediatric perioral dermatitis. Pediatr Ann. 2007;36(12):796–798.

4. Jansen T, Melnik BC, Schadenodorf D. Steroid-induced periorificial dermatitis in children—clinical features and response to azelaic acid. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27(2):137–142.

5. Zebda, Rema et al. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 78(3):S43-S52.

6. Liu D, Chow P, Strawn S, Rajpara A, Wang T, Aires D. Chronic nasolabial fold seborrheic dermatitis successfully controlled with crisaborole. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(5):577-578.

AUTHOR CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel Aires MD daires@kumc.edu