INTRODUCTION

Photography is essential in dermatology for longitudinal comparisons and referrals. While advancements in cameras and mobile phones/tablets have increased technology accessibility, these modalities are limited to two-dimensional (2D) imaging.1 Current advanced imaging technologies are often costly/impractical for most dermatology practices.2-4 Light/laser-imaging detection and ranging (LiDAR) measures the time taken for emitted infrared light to return to a sensor to create virtual, high-resolution, proportional three-dimensional (3D) models.5 Studies suggest LiDAR could be a cost-effective clinical tool.5 This study assesses the perceptions and feasibility of LiDAR compared to conventional photography for pre-operative dermatology assessments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

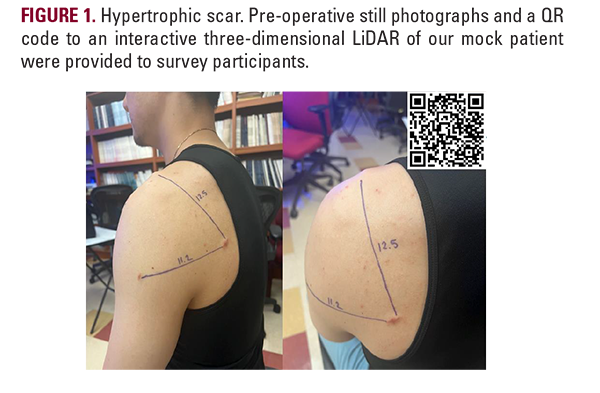

The IRB-approved survey was distributed electronically via the American College of Mohs Surgeons (ACMS) to US-based Mohs surgeons, fellows, and residents. The 18-item survey gathered information on practice setting, experience, pre-operative assessment protocols, and photography device usage. Participants evaluated a vignette using both a still photo (Figure 1A) and a LiDAR model (Figure 1B), rating the ease of use and likelihood of incorporating LiDAR in practice on a 5-point Likert scale (1=very difficult to 5=very easy). Data were analyzed via chi-square or Mann-Whitney U-test with post-hoc Holm-Bonferroni test, with P<.05 denoting significance.

RESULTS

Final analysis included 37 participants (Table 1) with 59.4% having over 10 years of independent practice, and 45.9% in group dermatology private practice settings. Tablets were the most used photo capture device (n=25; 67.5%; Table 1) with the Apple iPad being the most used tablet (n=24; 96%; Table 1). Whether referrals were accompanied by documentation was significantly associated with referral source (e.g., dermatologists vs non-dermatologists vs non-physician clinician, P<.001; Figure 2). If

referrals included documentation, they most commonly were clinical photographs without triangulations/markings among dermatologists (n=18; 48.5%) and non-physician clinicians (n=13; 35.1%; Figure 2). For non-dermatologist physicians, anatomical diagrams or patient charts with written descriptions or triangulations were more commonly provided (n=12; 32.4%, Figure 2).

Although majority (69.4%) of participants were unfamiliar with LiDAR and its availability on smart devices (91.9%; Table 1), participants reported similar interpretation ease between photographs (x̄=4.75) and LiDAR (x̄=4.63; Table 2). While LiDAR was rated easy to use among those unfamiliar with the technology (x̄=4.63; Table 1), participants were generally less inclined to adopt it into clinical workflow (x̄=2.00-2.71; Table 2). Dermatologists in academic/government/ university settings were more likely to consider using LiDAR for pre-operative planning (x̄=3.67) and patient and resident education (x̄=3.67) and in their surgical practice as a whole (x̄=3.67) compared to their colleagues, which were both significant with Bonferroni's Correction (P=0.04; Table 2).

Although majority (69.4%) of participants were unfamiliar with LiDAR and its availability on smart devices (91.9%; Table 1), participants reported similar interpretation ease between photographs (x̄=4.75) and LiDAR (x̄=4.63; Table 2). While LiDAR was rated easy to use among those unfamiliar with the technology (x̄=4.63; Table 1), participants were generally less inclined to adopt it into clinical workflow (x̄=2.00-2.71; Table 2). Dermatologists in academic/government/ university settings were more likely to consider using LiDAR for pre-operative planning (x̄=3.67) and patient and resident education (x̄=3.67) and in their surgical practice as a whole (x̄=3.67) compared to their colleagues, which were both significant with Bonferroni's Correction (P=0.04; Table 2).