practitioners were less likely to report that disaster preparedness should be included in dermatology training (64.2% versus 82.1%; P=0.0022; Figure 1). Dermatologists under 35 years of age were also less likely to feel that disaster preparedness should be part of their training compared to older practitioners (68.3% versus 80.1%; P=0.0266; Figure 1). A similar trend existed for dermatology residents, with only 66.7% reporting that disaster preparedness should be part of their training compared to 78.5% of dermatologists beyond residency, but the p-value did not reach significance (P=0.0527; Figure 1).

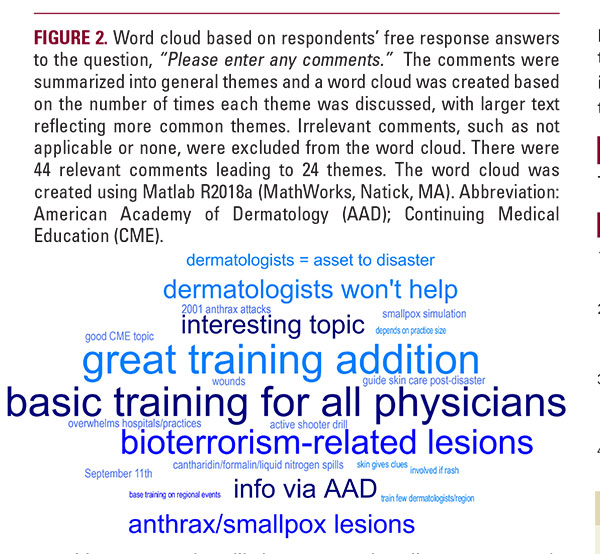

A common theme discussed in participants’ comments was that dermatologists should be prepared for bioterrorismrelated cutaneous disease (n=4), especially for anthrax- or smallpox-related disease (Figure 2). Others discussed that disaster preparedness would be a useful addition to dermatology training (n=5), possibly via the American Academy of Dermatology (n=3); yet, some respondents expressed reservations about dermatologists’ willingness to participate in a disaster response (n=3) (Figure 2).

Similar to the 2003 survey which showed that few dermatologists received adequate bioterrorism preparedness training,4 our survey found that a large percentage of dermatologists still have not received any type of disaster training. To examine training adequacy, we further evaluated dermatologists’ ability to manage the outcomes of specific disasters. We found that even with training, many dermatologists feel ill-prepared to manage patients affected by disasters, especially biological attacks and nuclear/radiological events. Given over 70% have not received training and the trained practitioners are still uncomfortable, the dermatology community is likely inadequately prepared for a disaster. Encouragingly, though, 75% reported that disaster preparedness should be part of dermatology training, thus a formal training program is sorely needed to meet this demand.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

1. Tempark T, Lueangarun S, Chatproedprai S, Wananukul S. Flood-related skin diseases: a literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52(10):1168-1176. doi:10.1111/ijd.12064

2. Farmer K, Proano L, Madsen JM, Partridge R. Introduction to Chemical Disasters. In: Ciottone’s Disaster Medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:639-643. https://www-clinicalkey-com.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/#!/content/ book/3-s2.0-B9780323286657001102. Accessed October 6, 2018.

3. Molé DM. Introduction to Nuclear and Radiological Disasters. In: Ciottone’s Disaster Medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:615-620. https://www-clinicalkey-com.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/#!/content/book/3-s2.0- B9780323286657001059. Accessed October 9, 2018.

4. Carroll C, Balkrishnan R, Khanna V, Feldman S. Bioterrorism preparedness in the dermatology community. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(12):1657-1658.

2. Farmer K, Proano L, Madsen JM, Partridge R. Introduction to Chemical Disasters. In: Ciottone’s Disaster Medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:639-643. https://www-clinicalkey-com.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/#!/content/ book/3-s2.0-B9780323286657001102. Accessed October 6, 2018.

3. Molé DM. Introduction to Nuclear and Radiological Disasters. In: Ciottone’s Disaster Medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:615-620. https://www-clinicalkey-com.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/#!/content/book/3-s2.0- B9780323286657001059. Accessed October 9, 2018.

4. Carroll C, Balkrishnan R, Khanna V, Feldman S. Bioterrorism preparedness in the dermatology community. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(12):1657-1658.

AUTHOR CORRESPONDENCE

Adam J. Friedman MD FAAD ajfriedman@mfa.gwu.edu